“Workers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains“

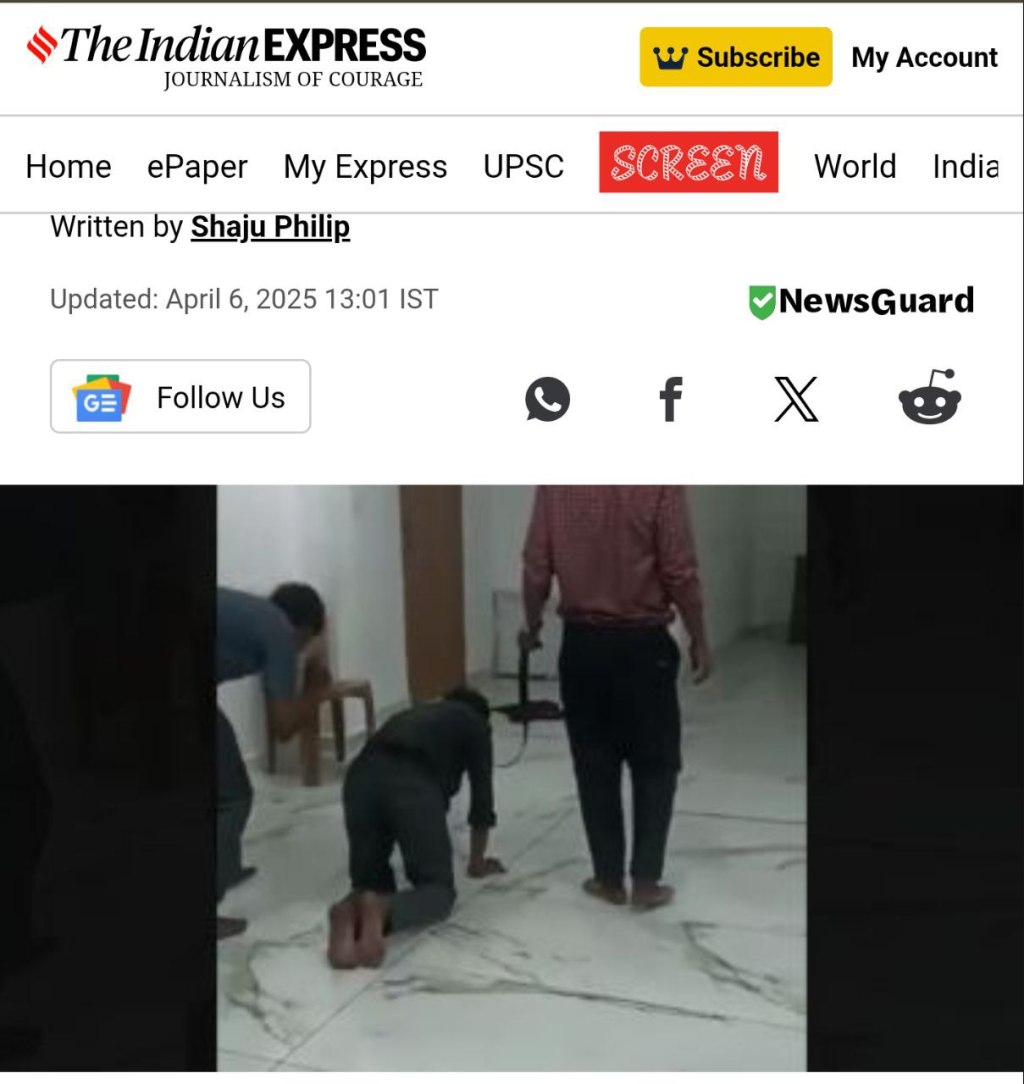

Recently, an incident in Perumbavoor caught national attention. Employees of a private company were reportedly forced to walk on all fours with a leash and lick things off the floor as punishment for not meeting sales targets. The outrage was immediate. What shocked many even more was that the video was six months old—and not a single employee had filed a police complaint.

This extreme case reveals a deeper, systemic problem. In a society where basic empathy should make such practices unthinkable, there still exists a group that justifies them. Libertarians, neoliberals, and free-market capitalists argue that since the company is privately owned, the employer can enforce any measures he pleases. After all, the workers are “free” to leave. Some even claim this is a win-win situation: the employee gets to survive, barely, while the employer gains a motivated workforce. They call it a voluntary trade, and thus, in their eyes, a good thing.

But how voluntary is a choice between starvation and humiliation?

Some are born into privilege, with access to food, education, and capital. Others are born into poverty, without even the means to build a future. In this system, if you can’t afford an education or seed capital to start a business, your options are brutally limited—പട്ടിണി or പട്ടിപ്പണി (starvation or exploitative work).

Neoliberals ensure this system stays intact. Their ideology is built around the belief that this is simply “how nature works”—the law of the jungle, the logic of evolution. Ironically, many of them reject religion but place a dogmatic faith in the so-called laws of the market.

They argue that to escape poverty, workers must simply “work harder,” endure the humiliations, and one day rise. We’ve already dissected this myth of meritocracy in our Ponman Analysis video.

But now, let’s look at a different story.

In 1943, Don José Maria Arizmendiarrieta, a priest who had narrowly escaped execution during the Spanish Civil War, founded a school for working-class boys in Mondragon, Spain. No youth from this town had ever been to university. Fr. Arizmendiarrieta wanted to change that. He emphasized both technical education and social values.

By 1956, eleven of his students had become engineers. With his encouragement, five of them and eighteen other workers started a cooperative factory making stoves. In 1959, they founded a cooperative bank. This bank became a cornerstone, funding the expansion of new and existing cooperatives.

This was no utopia on paper. It worked.

Mondragon grew into a federation of over a hundred enterprises, including eighty industrial cooperatives producing everything from machine tools and medical equipment to consumer goods and robotics. As of 2023, Mondragon reported €11.05 billion in sales and ranked among the top 10 largest companies in Spain. It remains the world’s largest worker cooperative network.

So what exactly is a worker cooperative?

In a typical capitalist firm, a few shareholders make the decisions while workers execute them. Power flows from the top down. But in a worker cooperative, the workers own the company. Each worker, regardless of role, has one vote. Decision-making is democratic. Profits are redistributed fairly. And studies show that co-ops are more productive, have higher survival rates (even in recessions), and deliver better wages and job satisfaction.

And they’re not limited to Spain.

In Kerala, India, successful worker co-ops include Kudumbashree, MILMA, and Dinesh Beedi Company. These were supported by proactive state policies like the Kerala Cooperative Societies Act of 1969, championed by the Achutha Menon government. Strong workers’ unions were instrumental in making these co-ops a reality.

Still, worker co-ops remain rare. Why? Because they’re hard to start. Workers often lack the capital to launch or buy out a company. That’s where governments must step in—with tax benefits, loans, and legal frameworks. In fact, studies show that co-ops formed through worker buyouts often outperform traditional firms. So Unions should be formed and promoted and Governments who acts for the welfare of workers should be elected.

We live in a world where neoliberalism dominates. Billionaires buy their eleventh private jet while the working class is told to be grateful for basic survival. This will not change—unless we act.

Worker cooperatives offer not just an economic model, but a moral alternative. A system where dignity, democracy, and equity replace hierarchy, humiliation, and exploitation.

Leave a comment